It is a strange irony that living with instant access to the sum of all human knowledge has led us to greater levels of uncertainty about almost everything. In a sea of information, it is difficult to know what – if anything – to believe. When faced with this problem, people cope in different ways. Some people attempt to remedy uncertainty by falling into one or more impenetrable information bubbles in which all dissenting opinions are vociferously shunned: notions are true if they are coming from “my team,” and false if they come from “the other team.” Things are much simpler that way. Others claim to trust nothing at all, based on the cynical premise that the truth is subjective, and we can’t really know anything for sure. The problem with both of these views is that they are equally lazy, and sometimes dangerous. When caught up in the cascade of information that we are subjected to every day, some may feel that they have neither the time nor the energy to sift through it all and engage in critical truth-seeking.

It takes dedication and drive to ask important questions about knowledge, e.g. how do I know that? What is this knowledge based on? Could it be wrong? Why do I personally believe x and not y? What are the biases of my sources? If I have been shown that one of my beliefs is wrong, what should I do now? These questions, while sometimes uncomfortable and difficult to answer, are still hugely worthy to think about, and we ignore them at our peril. Contemporary information systems such as social media, the 24-hour news cycle, and the ever-present influence of advertisers over the content we consume has led to an erosion of trust in experts. What we are left with is a sort of “decentralisation” of truth where anyone’s views, no matter how far removed from reality they are, can be validated and amplified by an “in-group” without critical examination. Disinformation has become easy to find and spread, and though it only takes a second to voice, disinformation can take a very long time to be convincingly debunked. In short, an absence of critical thinking can leave people vulnerable to manipulation. In the aforementioned sea of information, neglecting to think critically can leave one without a compass or a map. As a result, cynical forces that are more than willing to exploit people for political, financial, or social gain are empowered.

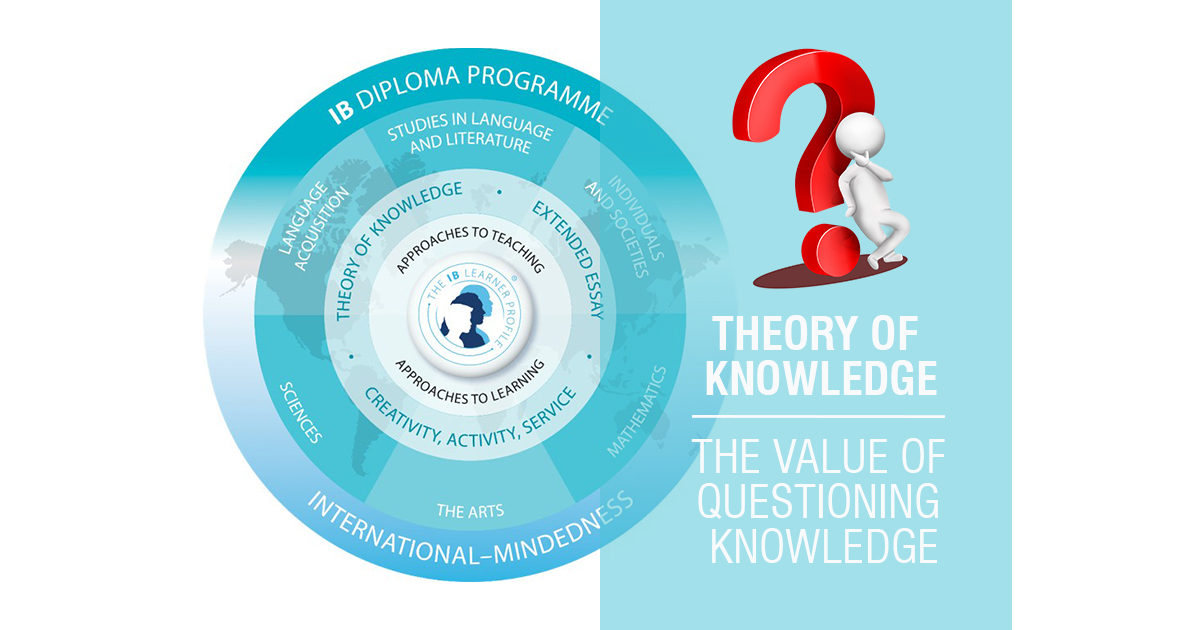

In the background of this rather grim assessment of the current state of information, I take my role as an educator very seriously. While I am incapable of ‘saving the world’ from disinformation, I feel that my role as an IB teacher enables me to do my part to foster critical thinking, however small a role I may play. What I have been most grateful for these past four years is the opportunity to teach what has become my favourite subject – Theory of Knowledge (ToK). This subject’s core question is how do we know what we know? and it serves as an introduction to critical thinking for young adults. It does this by asking more specific renditions of the questions I posed at the beginning of the previous paragraph. Students are required to begin the course with a thorough analysis of where many of their preconceived ideas about the world actually come from, and why they view them as knowledge. They are asked to consider what communities of knowers they belong to, and what influence this may have had on many of their perspectives. They are asked to consider the many facets of single issues, and what constitutes “good” evidence for any claim. Other components of the course give the opportunity for students to reflect on how knowledge is constructed, organised and viewed within academic disciplines which are familiar to them, such as the sciences, history, mathematics, and the arts.

Recently, the ToK syllabus underwent some fairly big changes. Students first assess their place in the world as knowers during our introduction theme called Knowledge and the Knower. Students then engage with two optional themes. This year, we have chosen Knowledge and Politics and Knowledge & Technology, two areas in which I believe young people must have a foundational awareness if they are to understand how knowledge is packaged, presented, and, at times, misused. Another change to the syllabus saw the introduction of an exciting task called the Knowledge Exhibition. While our first students to complete this task unfortunately had to do so online, we look forward to the public potential of this task if and when opening up the country becomes more viable in the future.

In the short time that I have been teaching ToK, I have had students both enlightened and frightened by the subject in roughly equal parts. Their experiences in my class opened them up to just how much contention exists just in the definition of the word knowledge. Having generally been used to subjects where knowledge is viewed as a body of facts and theoretical notions to be studied, looking deeper into the implications of this definition was new to almost all of them. Some have even recounted to me that they can no longer even view something so simple as a question in the same light again without considering its background, assumptions, basis, and the possibility of it having more than one answer. I am proud when I hear such assessments, because it means that they leave the course at least somewhat armed and armoured against disinformation in its many forms. It also means that I was able to play a small part in imparting the mission of the IB by fostering open-minded individuals who are also able to think reflectively and critically as they head into adulthood and independence.